As a liquid, solid or in gaseous form water is everywhere in the human environment: even in the driest deserts it rains at some time and they may become tangibly humid. Water vapour moves most quickly in the atmosphere because of continual circulation. But 99% of all the Earth’s gaseous water resides in the lowest part, the troposphere. In that layer temperature decreases upwards to around -70°C, reflected by the lapse rate, so that water vapour condenses out as liquid or ice at low altitudes in the tangible form of clouds. So as altitude increases the air becomes increasingly cold and dry until it reaches what is termed the tropopause, the boundary between the troposphere and the stratosphere. This lies at altitudes between 6 km at the poles and 18 km in the tropics. Higher still, counter intuitively, the stratospheric air temperature rises. This is due to the production of ozone (O3) as oxygen (O2) interacts with UV radiation. Ozone absorbs UV thereby heating the thin stratospheric air. The tropopause is therefore an efficient ‘cold trap’ for water vapour, thereby preventing Earth from losing its surface water. Any that does pass through rises to the outer stratosphere where solar radiation dissociates it into oxygen and hydrogen, the latter escaping to space. So for most of the time the stratosphere is effectively free of water.

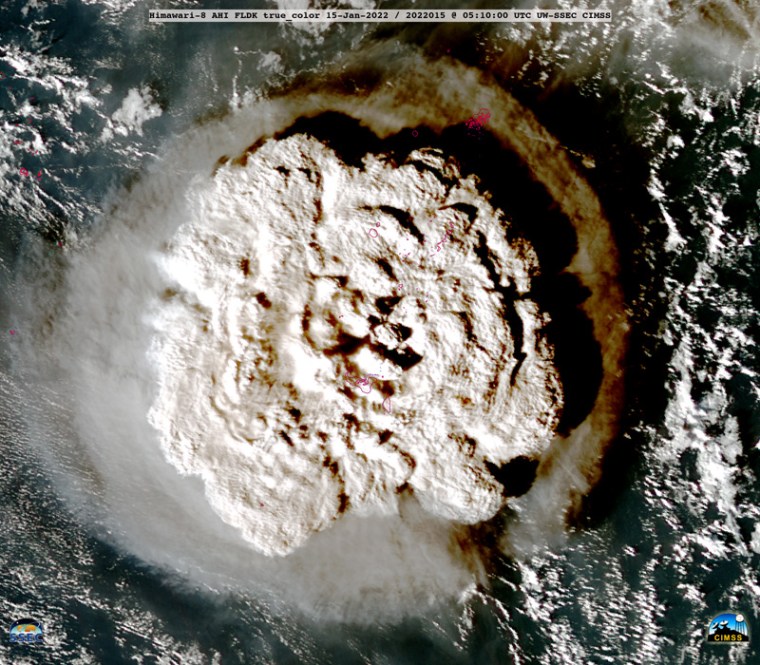

On 14 to 15 January 2022 the formerly shallow submarine Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano in the Tonga archipelago of the South Pacific underwent an enormous explosive eruption (see an animation of the event captured by the Japanese weather satellite Himawari-8). The explosion was the largest in the atmosphere ever recorded by modern instruments, dwarfing even nuclear bomb tests, and the most powerful witnessed since that of Krakatoa in 1883. But, as regards global media coverage, it was a one-trick pony, trending for only a few days. It did launch tsunami waves that spanned the whole of the Pacific Ocean, but resulted in only 6 fatalities and 19 people injured. However, Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai managed to punch through the tropopause and in doing so, it changed the chemistry and dynamics of the stratosphere during the following year. A group of researchers from Harvard University and the University of Maryland used data from NASA’s Aura satellite to investigate changes in stratigraphic chemistry after the eruption (Wilmouth, D.M. et al. 2023. Impact of the Hunga Tonga volcanic eruption on stratospheric composition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, v. 120, article e23019941; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2301994120). The Microwave Limb Sounder (MLS) carried by Aura measures thermal radiation emitted in the microwave region from the edge of the atmosphere, as revealed by Earth’s limb – seen at the horizon from a satellite. Microwave spectra from 0.12 to 2.5 mm in wavelength enable the concentrations of a variety of gases present in the atmosphere to be estimated along with temperature and pressure over a range of altitudes.

The team used MLS data for the months of February, April, September and December following the eruption to investigate its effects on the stratosphere n from 30°N to the South Pole. These data were compared with the averages over the previous 17 years. What emerged was a highly anomalous increase in the amount of water vapour between 0 and 30°S (the latitude band that includes the volcano) beginning in February 2022 and persisting until December 2023, the last dates of measurements. By April the peak showed up and persisted north of the Equator and at mid latitudes of the Southern Hemisphere and by December over Antarctica. It may well be present still. The estimated mass of water vapour that the eruption jetted into the stratosphere was of the order of 145 million tons along with about 0.4 million tons of SO2, the excess water helping accelerate the formation of highly reflective sulfate aerosols. Associated chemical changes were decreases in ozone (~ -14%) and HCl (~ -22%) and increases in ClO (>100%) and HNO3 (43%). Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai therefore changed the stratosphere’s chemistry and a variety of chemical reactions. As regards the resulting physical changes, extra water vapour together with additional sulfate aerosols should have had a cooling effect, leading to changes in its circulation with associated decrease in ozone in the Southern Hemisphere and increased ozone in the tropics. Up to now, the research has not attempted to match the chemical changes with climatic variations. The smaller 15 June 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo on the Philippine island of Luzon predated the possibility of detailed analysis of its chemical effects on the stratosphere. Nevertheless the material that is injected above the tropopause resulted in a global ‘volcanic winter’, and a ‘summer that wasn’t’ in the following year. The amount of sunlight reaching the surface fell by up to 10%, giving a 0.4 decrease in global mean temperature. Yet there seem to have been no media stories about such climate disruption in the aftermath of Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai. That is possibly because the most likely effect is a pulse of global warming in the midst of general alarm about greenhouse emissions, the climatically disruptive effect of the 2023 El Niño and record Northern Hemisphere temperature highs in the summer of 2023. Volcanic effects may be hidden in the welter of worrying data about anthropogenic global climate change. David Wilmouth and colleagues hope to follow through with data from 2023 and beyond to track the movement of the anomalies, which are expected to persist for several more years. Their research is the first of its kind, so quite what its significance will be is hard to judge.