Detrital zircon grains extracted from sandstones deposited ~3 billion year (Ga) ago in Western Australia yield the ages at which these grains crystallised. The oldest formed at about 4.4 Ga; only 150 Ma after the origin of the Earth (4.55 Ga). Various lines of evidence suggest that they originally crystallized from magmas with roughly andesitic compositions, which some geochemists suggest to have formed the first continental crust (see: Zircons and early continents no longer to be sneezed at; February 2006). So far, no actual rocks of that age and composition have come to light. The oldest of these zircon grains also contain anomalously high levels of 18O, a sign that water played a role in the formation of these silicic magmas. Modern andesitic magmas – ultimately the source of most continental crust – typically form above steeply-dipping subduction zones where fluids expelled from descending oceanic crust encourage partial melting of the overriding lithospheric mantle. Higher radiogenic heat production in the Hadean and the early Archaean would probably have ensured that the increased density of later oceanic lithosphere needed for steep subduction could not have been achieved. If subduction occurred at all, it would have been at a shallow angle and unable to exert the slab-pull force that perpetuated plate tectonics in later times (see: Formation of continents without subduction, March, 2017).

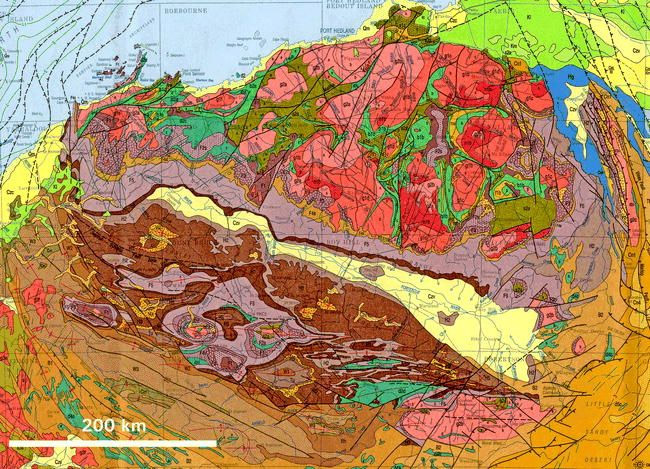

Geoscientists have been trying to resolve this paradox for quite a while. Now a group from Australia, Germany and Austria have made what seems to be an important advance (Hartnady, M. I. H and 8 others 2025. Incipient continent formation by shallow melting of an altered mafic protocrust. Nature Communications, v. 16, article 4557; DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-59075-9). It emerged from their geochemical studies of rocks in the Pilbara Craton of Western Australia that are about a billion years younger than the aforementioned ancient zircon grains. These are high-grade Palaeoarchaean metamorphic rocks known as migmatites that lie beneath lower-grade ‘granite-greenstone’ terrains that dominate the Craton, which Proterozoic deformation has forced to the surface. Their bulk composition is that of basalt which has been converted to amphibolite by high temperature, low pressure metamorphism (680 to 730°C at a depth of about 30 km). These metabasic rocks are laced with irregular streaks and patches of pale coloured rock made up mainly of sodium-rich feldspar and quartz, some of which cut across the foliation of the amphibolites. The authors interpret these as products of partial melting during metamorphism, and they show signs of having crystallised from a water-rich magma; i.e. their parental basaltic crust had been hydrothermally altered, probably by seawater soon after it formed. The composition of the melt rocks is that of trondhjemite, one of the most common types of granite found in Archaean continental crust. Interestingly, small amounts of trondhjemite are found in modern oceanic crust and ophiolites.

The authors radiometrically dated zircon and titanite (CaTiSiO₅) – otherwise known as sphene – in the trondhjemites, to give an age of 3565 Ma. The metamorphism and partial melting took place around 30 Ma before the overlying granite-greenstone assemblages formed. They regard the amphibolites as the Palaeoarchaean equivalent of basaltic oceanic crust. Under the higher heat production of the time such primary crust would probably have approached the thickness of that at modern oceanic plateaux, such as Iceland and Ontong-Java, that formed above large mantle plumes. Michael Hartnady and colleagues surmise that this intracrustal partial melting formed a nucleus on which the Pilbara granite-greenstone terrain formed as the oldest substantial component of the Australian continent. The same nucleation may have occurred during the formation of similar early Archaean terrains that form the cores of most cratons that occur in all modern continents.